My Neighbor, the Bigleaf Maple Tree

- cindyinthewild

- Apr 13, 2021

- 4 min read

Ever since the day I first moved into my cabin, I wanted to get to know the tree standing right outside my window. I noticed big leaves the size of my hand and odd little seeds that people here call "helicopter leaves". It was my first time in the Pacific Northwest, which is a stark difference compared to where I am from in Houston, Texas. Over the next few months, I came to learn more about this tree and its much older, taller siblings on IslandWood campus.

What is the bigleaf maple tree?

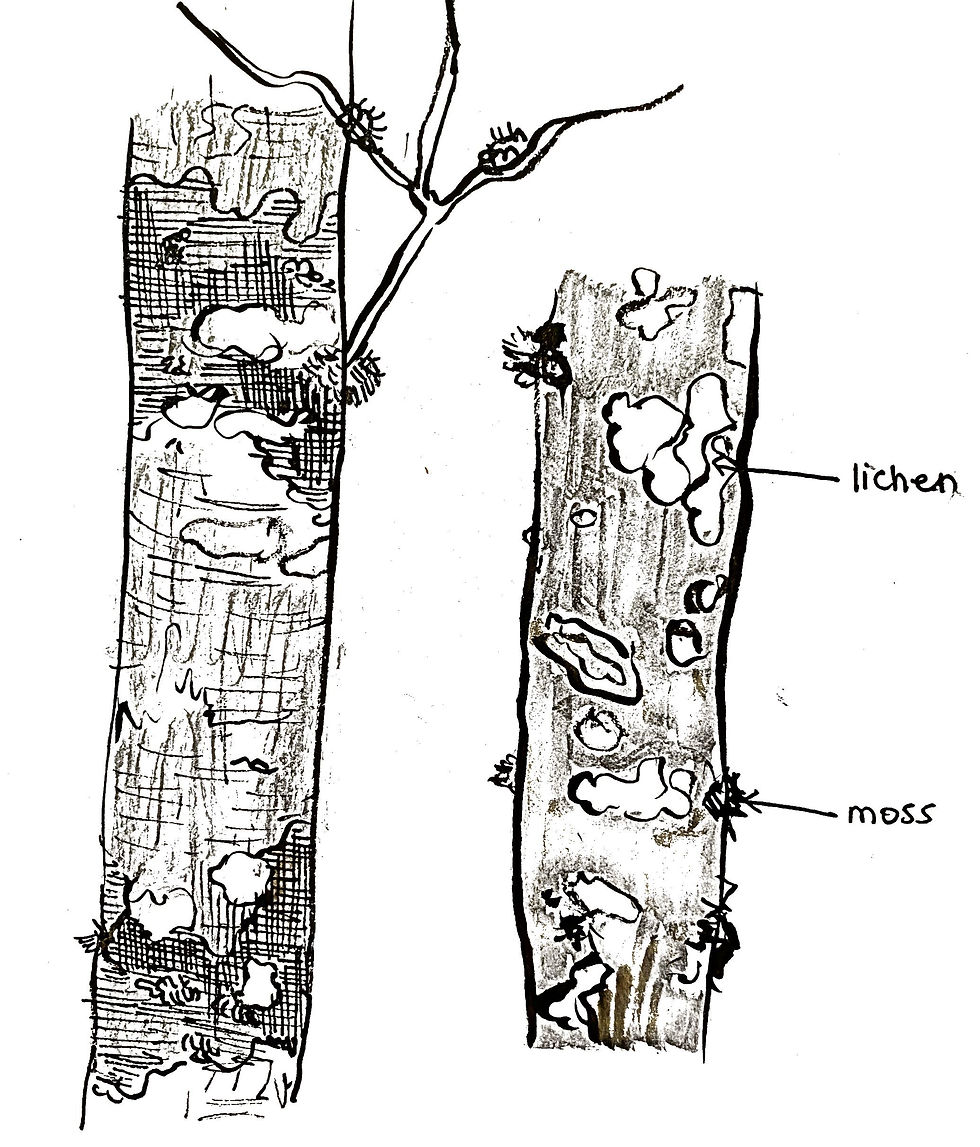

Bigleaf maple trees are deciduous trees that are native to the “west coast of Turtle Island (North America) between southern Alaska and San Diego, California” (Wong, 2019). They can reach upwards of 116 feet in height and survive up to 200 years of age. They are often covered in moss, from the bottom of their trunks all the way to the highest branches. More moss can be found on these trees than on any other trees of the Pacific Northwest (MacKinnon, Pojar, & Alaback, 1994). Young bigleaf maple bark is grey-green and smooth, which I have noticed in the young tree next to my cabin (pictured to left and below), whereas most of older trees on IslandWood’s main campus are textured in furrows and look more brown.

The flowers of the trees provide nectar sources for native insects and honeybees starting in mid-spring. Their leaves can grow quite large (from 6 to 12 inches across) and also have five lobes, resembling a human hand. They also have winged seeds that form in the late summer, commonly called helicopter leaves for the unique way they spin in circles as they fall. I learned that bigleaf maple begins to produce seeds at around 10 years of age, meaning the tree next to my cabin must be at least over 10 years old (Wong, 2019).

How did I get to know my neighbor?

Whenever I walk to my cabin during the day, I notice the tree because it is so visible, standing right next to the side.Growing up, I had always wanted a tree right in my backyard. I take pictures of it often. I look at its branches and leaves from my windows frequently from inside my cabin. Back in the summer, I noticed its fullness - green leaves and all. Squirrels would climb up on its branches for a meal. Birds would find a nice spot to land on it before flying off to their next destination. I still had not yet gotten a close eye on the tree, so I decided to sit right next to it for my nature field journal. I loved to sit underneath the shade of its leaves.

Over time as I experienced my first Pacific Northwest fall, its leaves changed colors. Around mid-October, I noticed only the leaves at the top began to turn yellow. By end of October, the leaves were mostly warm colors. Brown and crinkled leaves began to cover the ground underneath it. I started to observe its trunk, the textures and colors of the bark. I felt the tree’s sturdiness when I placed my hand on it, in effort to connect with it more. It feels so rooted in the ground. In just the past two weeks of November, 95% of the leaves have fallen, with only samaras still hanging onto its branches. What I have most enjoyed when observing the tree has been during the rain. I love watching the water flow down from the branches, with moss clumps holding the water and raindrops trickling down from the bark. I have also noticed the color of the bark appears differently after a rain - much more deep brown and moving, making its white spots more visible. I have documented these changes over time in my field journal, and hope to continue noticing how it changes through the winter season.

Significant Cultural Connections and Ethnobotanical Use

In many Indigenous languages and dialects, the meaning of this tree’s name is “paddle tree”, “which emphasizes its importance as it is one of the only durable hardwood species on the coast.” (Wong, 2019)

The bark of the tree is a very versatile material. Its wood can be carved into “masks, clubs, tool handles, dishes, spoons, hair combs, rattles. fish lures, hooks, and snowshoe frames” (Wong, 2019), used to make furniture and musical instruments (Pojar & MacKinnon 1994). Even dead wood can be used by the Swinomish, by Chehalis and Quinalt for smoking salmon. (MacKinnon, Pojar, & Alaback, 1994).

Medicinal uses: The Klallam boil the bark and drink the mixture for treating tuberculosis (MacKinnon, Pojar, & Alaback, 1994) while the Lower Nlaka’pamux people in the Fraser Canyon made maple syrup as a tonic and sweetener (Wong, 2019).

Teaching Connections

I have had students engage with the helicopter leaves, or samaras, of the bigleaf maple trees. The trees that are on Islandwood’s main campus are plentiful. They are also huge and tall and more fully grown than the one that grows next to my cabin. The drop investigation is a classic lesson for students at IslandWood’ Suspension Bridge, where many maple leaves and helicopter leaves collect onto the ground and bridge. I would invite students to collect the helicopter leaves (or “helicabopters”) and drop them into the ravine below. I ask them questions about how fast they think one leaf might fall compared to another based on its shape or texture. The students are quick to try new ways of sending off their leaves, whether it means throwing a whole bunch of them at once, tying them to maple leaves, or doing leaf races. During this activity, my co-teacher and I will ask questions about what happens to the leaves when they reach the ground, where they think the leaves come from, and for what reasons the seeds are made to fly away so far. All students I have taught find this to be the most fun part of the week because they love watching how the leaves spin around and down from the bridge as it falls from their hands.

Comments